My view of what discipline is recently took a shift.

For a long time, I would say I knew what discipline looked like. It looked like doing the things you're "supposed" to do and not doing the things you're not supposed to do.

It looks like reading or writing instead of playing video games.

It looks like waking up early to get after it instead of partying all night.

It looks like not dilly dallying on your phone when you have better things to do.

The list goes on...

I've gotten somewhat disciplined over the years by understanding this and doing my best to act out that discipline. But, there's a difference between knowing how to act and having a better understanding of the underlying structure of what's going on.

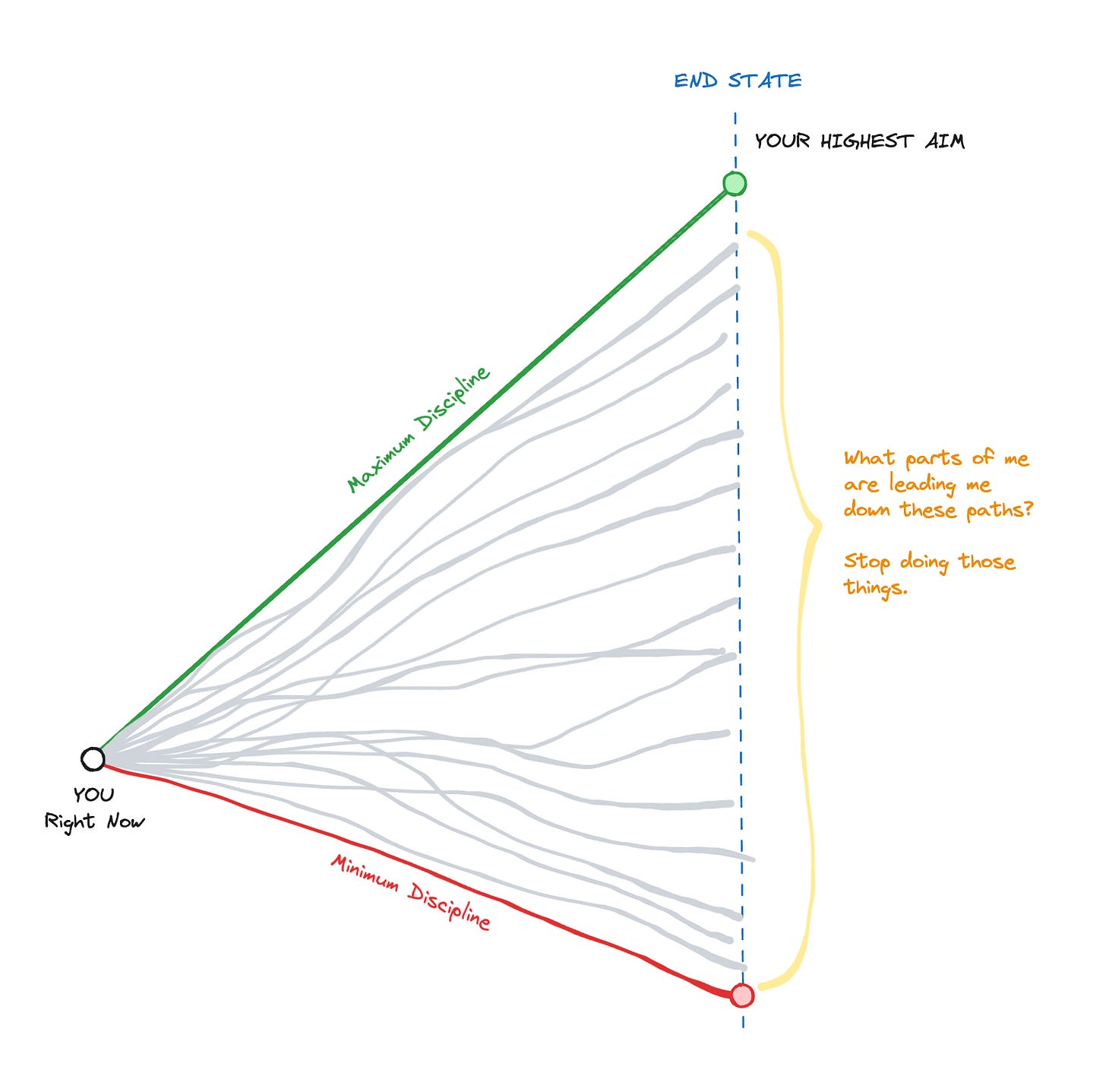

What discipline appears to me to be now is the process of eliminating from myself personality or my life those things that are getting in the way of my highest possible aim. I've got an aim, at least a direction, of who I want to be and what I want to grow in to. Then I try think about:

What do I do that gets in the way of that?

What are the things I do that do not contribute to that goal?

What do I do to make the possibility of achieving this aim as likely as possible?

There are things about myself that I need to get rid of if I want to achieve my highest possible aim. And more importantly, there always will be. Because I'm not perfect, and I never will be.

So, I work to identify those things I need to stop doing and then stop doing them, to the best of my ability. Then, over time, as I continue to eliminate more things from my life that don't align with my aim, I should continually become more disciplined, aligning everything I do with my aim.

Ties to Jocko & Peterson

I think this concept ties into lessons I've heard from both Jocko and Jordan Peterson.

In one podcast Jocko is addressing why discipline is hard to maintain. After he clarifies that discipline is and always will be hard, he goes on to describe the one thing that he believes can make discipline easier:

If there's one thing I would say that does make it easier, it's to envision what it feels like when you're done. What it feels like after you've worked out, or you've held the line on your food intake, or you've pushed through some monotonous project that you have to do. In all those things, when they're done, they feel good. And contrary to that, envision what you will feel like later when you let the discipline slack. You know the feeling–feeling weak and defeated, and you know that you're falling behind.

So, get to know those two different types of feelings, and ask yourself–which one you want to feel in ten minutes? Or in a half an hour? When when the thing is done. When the discipline has been implemented. Remember what that feels like. And then remember that those minutes, and those hours, they turn into weeks, and months, and years. And holding the line in those critical minutes will put you in an infinitely better place physically and mentally if you maintain the discipline.

One of the things Jocko is getting at here is thinking about where you want to be, what you're aiming at, and recognize that what you do in each hour of every day either builds toward that aim or it doesn't. By thinking about what it will feel like in the long haul if you don't maintain the discipline, it makes it slightly easier in that moment to execute on those things that you should.

Jordan Peterson approaches this same concept in his Future Authoring course. Jordan's description of future authoring mirrors what Jocko is talking about but with a longer timeline, on the scale of years rather than hours. Jordan describes part of the exercise on Theo Von's This Past Weekend #328 is to ask:

If you were to deteriorate according to your own vices and that got out hand, what would that look like five years down the road?

This question prompts you to identify the parts of you that would be better if they were dead or kept in check to ensure you don't end up in a potential hell in your future. The future authoring program also has you write out your ideal future as well, resulting an a better understanding for yourself of both where you want to be aiming and where you don't want to go. Then, you can start eliminating those things from your life that don't build toward that ideal future.

Closing thoughts

Maybe at the end of the day what I'm looking at here is two sides of the same coin. One side is doing the "right things" instead of the wrong things. The flip side is eliminating everything that does not contribute to your aim (the wrong things) and eliminate those, which results in you doing what you need to be doing to achieve your aim (the "right things").

I think that frame is more effective for me because it prompts me to face the implications of inaction. The implications of where I end up if I don't maintain the discipline. Because that lack of discipline would not just effect my own life negatively. It effects my family, my colleagues, and my community.

Now, this is all obviously easier said than done. Hence Jocko's continual emphasis on the fact that "the reason discipline is hard is because its hard". But, this framework of discipline has helped me tremendously in the last few months, and I hope to continue to use this frame to get better moving forward.