"You are the General that is in charge of your life." - Jocko Willink

The Framework

Jocko Willink has been releasing a series of videos he calls Standard Directives. In his second Standard Directive video, he describes how you are the general of your life. He describes that as the general, you are the one who decides what you're' going to do, and how you're going to do it. You come up with the strategy and the tactics, and you give the orders to the troops.

"But", Jocko says, "you are also the troops." You are the soldier that is responsible for the execution of the orders that are given to you by the general.

I love this framework, and it got me thinking on a few things.

Wasted Time

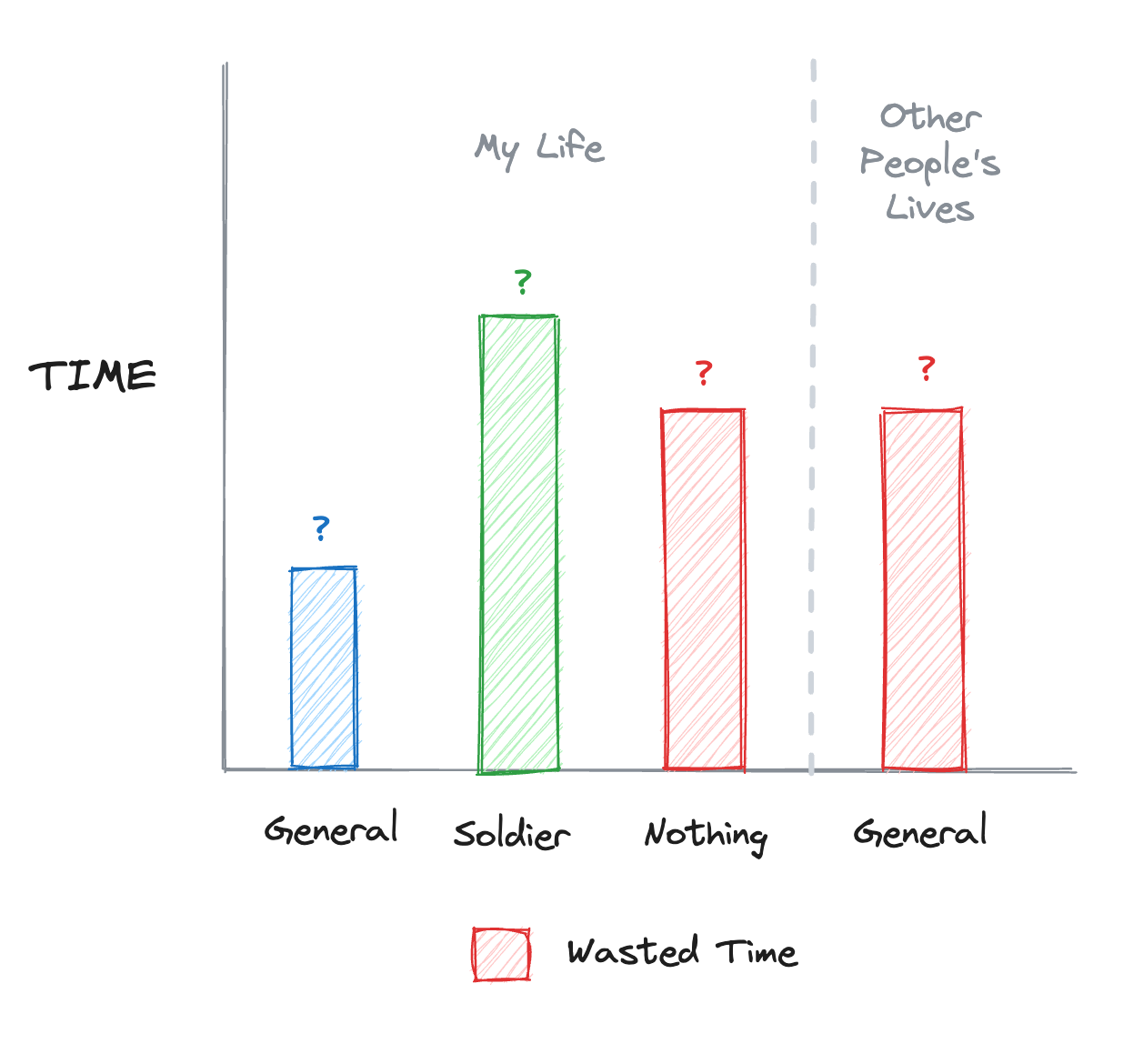

How much time do I spend being the general versus the soldier in my own life?

The ugly truth sets in quickly. If I add up my time spent as the general and the soldier in my own life, the two combined are a far cry from 100% of my time.

There's times where I'm doing neither, and that's a lack a discipline.

Even worse, there's times where I play the fictional general for other people's lives. Every minute I spend being the fictional general of someone else's life is precious time wasted that could have been spent being the general for my own. There's certainly plenty of work to be done on that front in my life.

Why is it so easy to fall into the act of being the fictional general or simply doing nothing? What causes me to avoid being the soldier and the general of my own life?

Avoiding Being the General

Why are there times I avoid being the general of my own life? As I think about this question, a few realizations come to me:

1. It's a burden.

2. It requires setting conditions for failure.

1. It's a burden.

Jordan Peterson defines adulthood as the realization that no one knows what you should do better than you do. This is a tough reality to handle, so tough in fact that some of us never truly come to it. But, I believe it is a good definition. The implications of this definition is that you, as the general of your own life, are the best general for your life. We have to accept the burden and the weight of that responsibility.

For the big decisions in our lives, the ones that have a lasting impact, the "right" answer is not always obvious. What career should I pursue? Which one of my many inadequacies should I fix first? There's an endless stream of questions without a sure solution. Despite the uncertainty, we have to be the ones to make those decisions. No one else knows better than us what the best path forward is.

Admiral William McRaven sums up a strategy to deal with this situation in his book "The Wisdom of the Bullfrog". The Admiral breaks down a mantra coined by Admiral Chester Nimitz, "When in command, command!" saying:

"On those days when I felt indecisive, when I took too much counsel of my fears, when worry threatened to stall my actions, I hearkened back to Nimitz's words: 'When in command, command!' And with those words as my guide, I always tried to do right by the women and women who served with me."

2. It requires setting conditions for failure.

As the general, my job is define the mission and give the orders to the troops to execute on. By defining the missions and the goals associated with them, I cannot avoid also setting the conditions for failure.

This leads me to avoid the action of being the general completely. If I don't set the mission and the goals, I'm able to avoid failing to accomplish that mission in the future.

It's important for me to remember here that failure is relative. Whether I fail in a particular endeavor or succeed, the important lesson to walk away with is learning how to calibrate my future goals. If I fail, what caused that failure? Was the goal too lofty? If I succeed, was the goal to low?

Failing is nothing new for me, I've done it over and over again. Use the outcomes to hone in my skills as a general, and I'll surely be better for it.

Avoiding Soldiering

What prevents me from being the best soldier in my own life?

1. I don't understand the why.

2. There's no guarantee for success.

1. I don't understand the why.

I think we all know this feeling. I've been tasked to do something, maybe by a coach or a boss, but I haven't bought into why I even should be doing this thing in the first place. Because of this lack of understanding, I don't give it our all out effort. I half-ass things, or maybe even completely avoid doing them at all.

As the general, I've got to define the why for the soldier. And as the soldier, I have to buy in to that why. I have to believe the mission is a mission worth executing.

Defining this why can quickly slide me into the rabbit hole of the question "why do anything?" It's a worthwhile question, and one I'll likely dive into more in the future.

But in the meantime, the primary truth for me to remember is that I know that I can be better. I have countless faults. I have no shortage of wisdom to gain, and I'm far from perfect. That means I have room to grow, room to be better. And that has a direct effect on not only the quality of my life, but my family's lives and community beyond that. So as long as the mission is leading me forward, it's a worthwhile endeavor.

2. There's no guarantee for success.

Executing on the orders handed down by the general takes energy. The loftier the mission and goals defined by the general, the more effort and energy it will take to execute on them. And on top of that, there's no guarantee that the effort and energy I put in will result in a mission accomplished.

The future is unpredictable, the world is chaotic. And because of that, there's many factors that contribute to our overall success that are out of my control.

It's interesting to see that I appear to fear failure from the perspective of both the general and the soldier. This is echoing the points made in the earlier section.

From the soldier's perspective, I'm reminded of Ryan Holiday's mantra of "the effort has to be enough". We have to accept that despite all the external factors that are out of our control, it's still our duty to control what we can control and strive to accomplish the mission that has been laid before us. Put in the effort, and take the time to learn from either the success or failure.

Closing Thoughts

How much farther in life could I get faster if I stop wasting time in the nothing or fictional general buckets? It's worth finding out, and it leads to a better future for me and all those around me. Looks like I've got some work to do.